Harting’s first intentional archaeological excavation was undertaken in 1934 by a retired schoolmaster from Fareham, Hampshire, called W A Gilmour. While on a visit to Harting he had been told by the then Rector, A J Roberts, about a place on the Downs, close to the parish boundary, where Roman coins & Samian ware had been found. Having obtained the permission of the landowner, at that time Admiral Sir Herbert Meade-Fetherstonhaugh of Uppark, he began operations. It was not the most promising of starts – the site was running to scrub, and the numerous roots caused him to give up after only a brief exploration without finding any significant features. Undeterred by this disappointment, however, he moved several hundred yards to the north, and began again on another possible Roman site at the head of a small valley in the Downs called Bramshott Bottom. The rest of his career as an amateur archaeologist was to be spent digging this second site exhaustively.

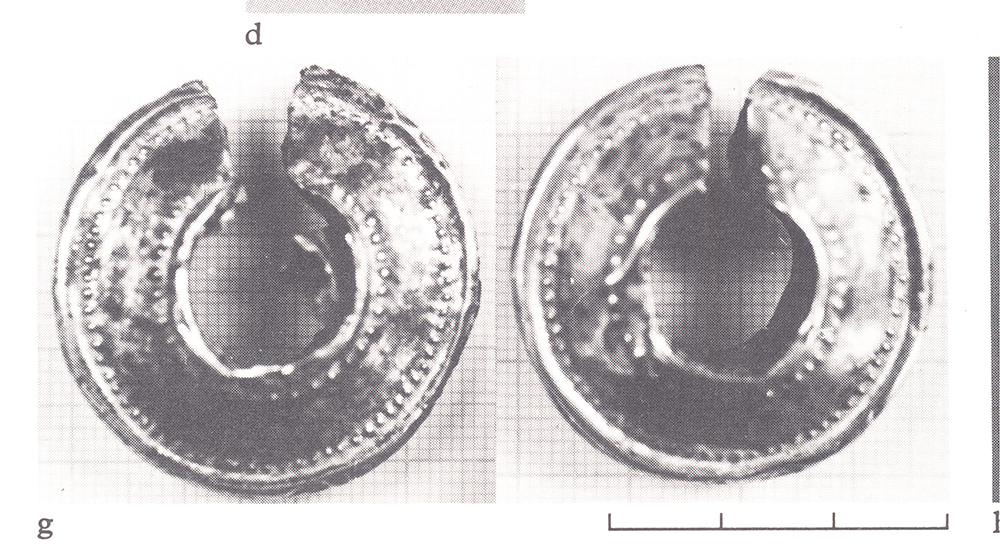

Unbeknownst to Gilmour his activities had been closely watched by a local builder’s labourer named Horace Brightwell. Once Gilmour had abandoned his first site, Brightwell moved in and continued to dig. It is possible that nothing may have come of this piece of archaeological poaching, had Brightwell not found a rare Iron Age blue glass bead, which he took to show the Rev A J Roberts. Roberts then sought to get it published without reference to Gilmour, an almost unforgiveable sin in the world of archaeology, and thus started a bitter verbal war of ownership which was to continue until Gilmour’s death in 1944. Brightwell even went to the length of naming his house “Bead Cottage” in a pointed statement of defiance.

All this is a rather long-winded way of answering one of the questions raised by my previous blog concerning what happened in Harting after the abandonment of the hillfort on Torberry Hill sometime around 100BC. For what Brightwell had found was the first clear evidence in Harting of a Late Iron Age artefact in close association with Roman finds. Gilmour was to go on to find many more, with his site at Bramshott Bottom producing a significant number of Iron Age coins amongst those of the Roman period. And this picture is by no means unique, for the majority of the Roman sites now known in the parish follow the same pattern, with their earliest known artefacts belonging to the first century BC and continuing on well into the Roman period, and in some cases beyond. What we don’t know is whether these sites go even further back, with Middle Iron Age origins contemporary with Torberry Hill, and this uncertainty is because only the two sites mentioned above have been excavated and neither of these was ever properly reported on.

However, our knowledge of Roman Harting is not restricted to merely the activities of Gimour and Brightwell. One of the big advantages of the increase in trade and technology that came with the Late Iron Age and Roman period is that there was a concomitant increase in the amount of stuff that everyone had. This in turn results in an awful lot more rubbish being generated, which then finds its way into the ploughsoil of our fields today. This means that sites of this period are considerably easier to find than those of almost any era of the past, and our map of Roman Harting is therefore much more densely filled. But there are two restrictions on this – first, to find a site it has to have been ploughed or disturbed in some way and secondly someone who knows what they are looking for needs to have been there to look.

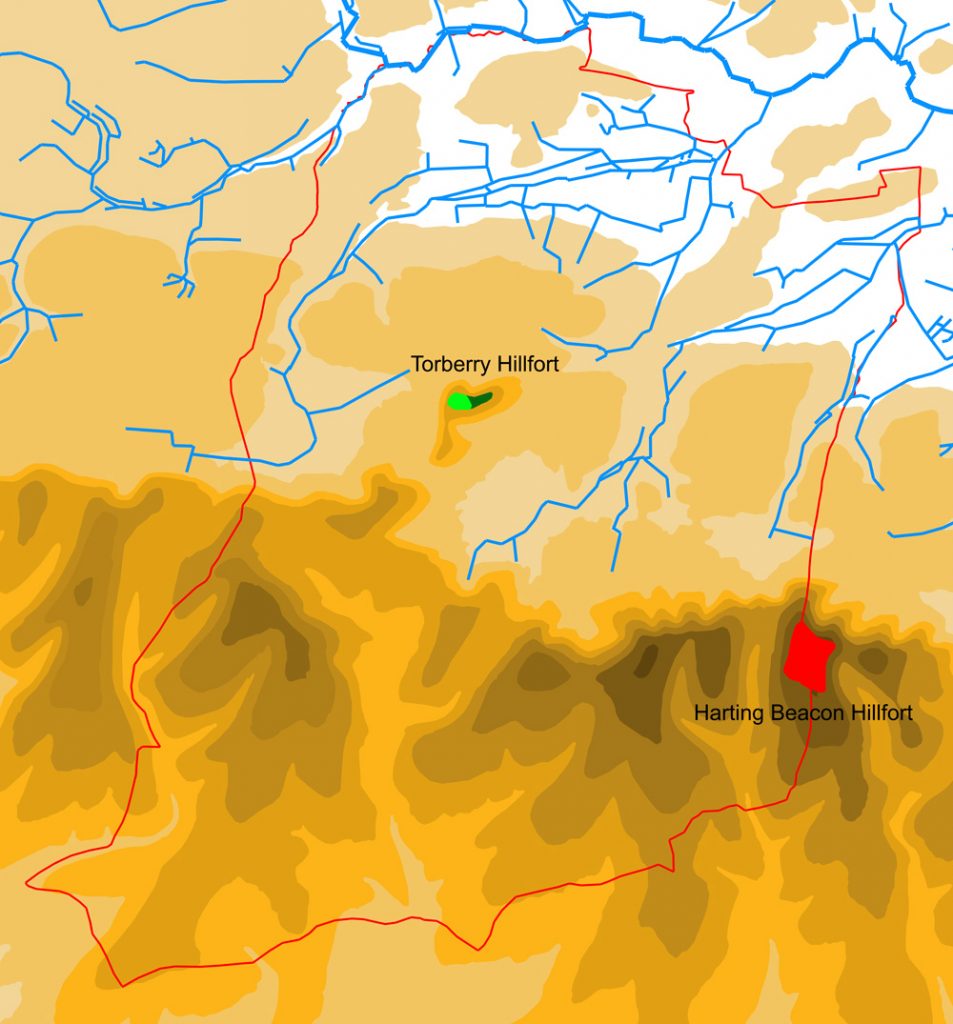

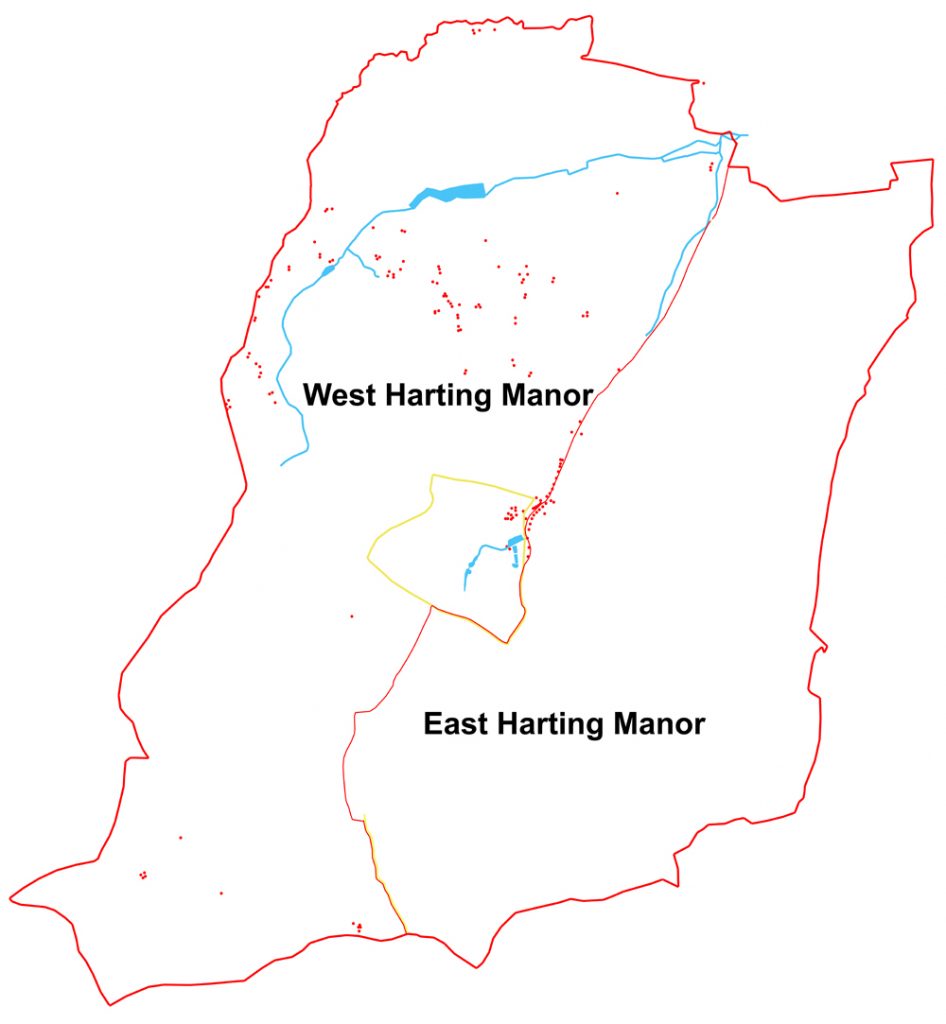

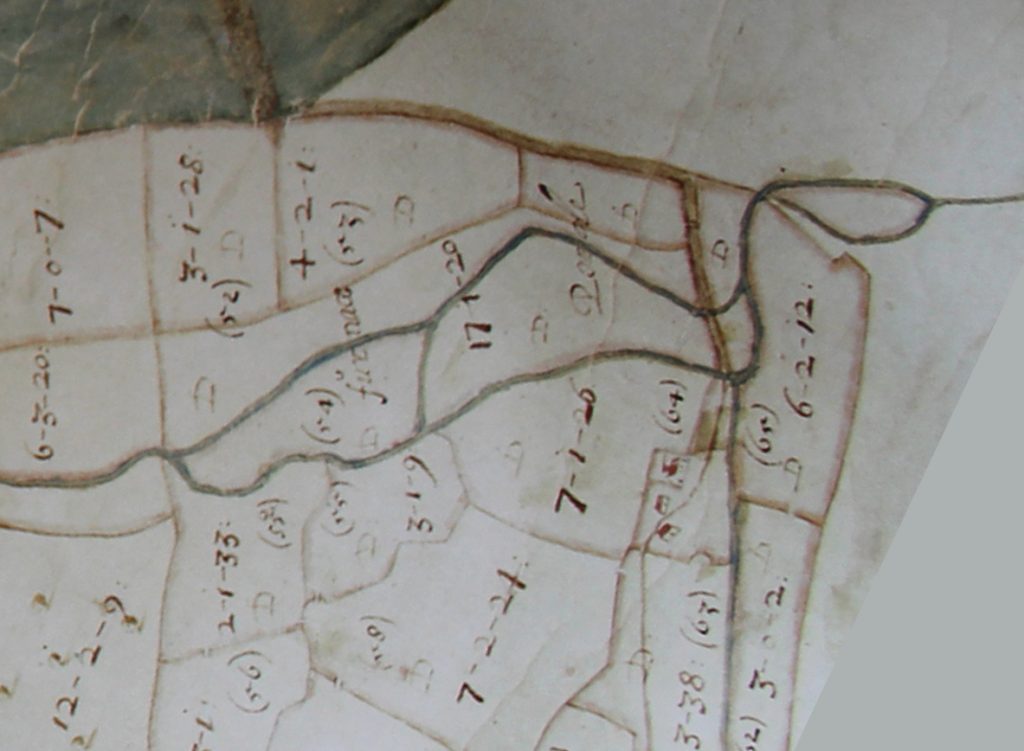

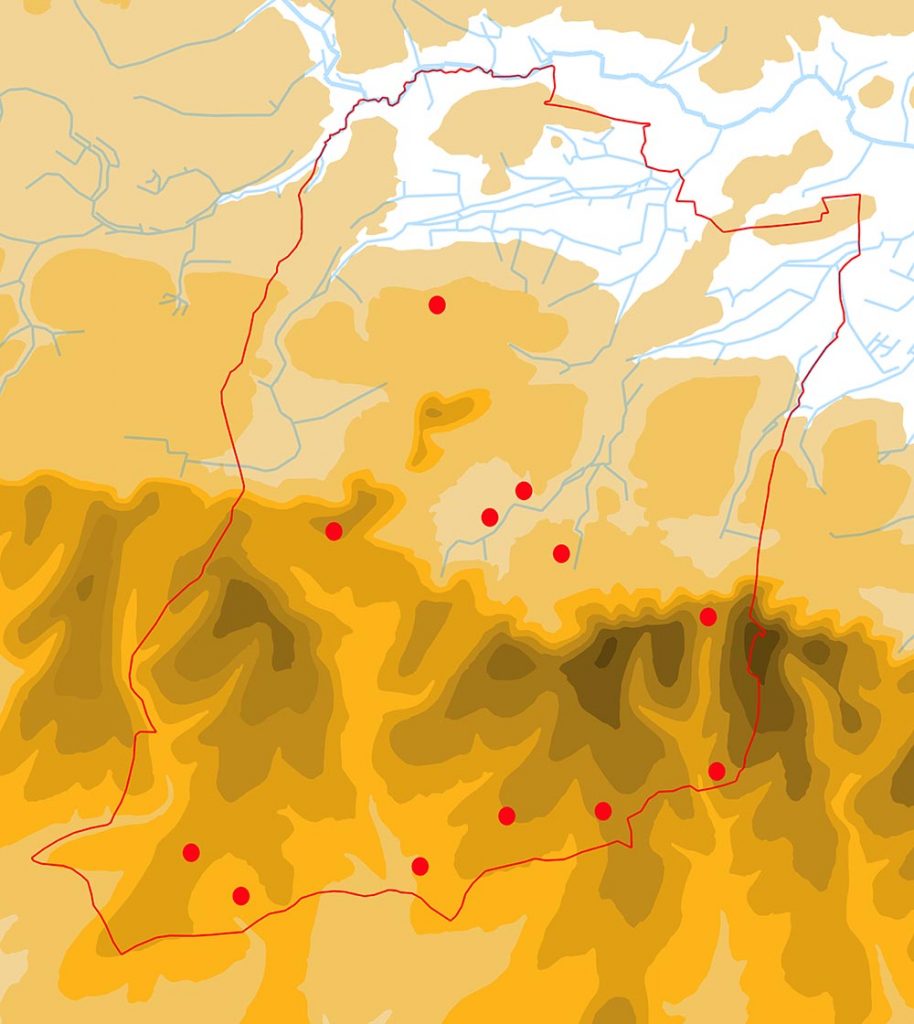

The map below shows all the currently known Late Iron Age/Roman sites in the parish, and their distribution perfectly reflects the results of the restrictions mentioned above. The collection of five sites in the south-east part of the parish are all known from finds made in ploughsoil, mole-hills or rabbit burrows and all were discovered many years ago when previous owners of the Uppark Estate had close links to archaeologically-minded Rectors, or their friends, who were, it seems, permitted to roam almost at will. Included amongst these are the sites Gilmour and Brightwell investigated. The four sites on the west side of the parish were all located by metal-detectorists, at least three a product of large-scale detecting “rallies”. But only some landowners will allow detectorists access, and so such intense seeking activity is patchy across the parish.

With the exception of Gilmour’s site at Bramshott Bottom, which would appear to be a small farmstead, it is not known exactly what type of Roman site these all are, but they are likely to be either other farmsteads or small villas (the difference between the two is rather imprecise anyway, largely being define nowadays by whether the site has a timber or stone principal dwelling). But the cluster of three sites in the centre of the parish, lying within the village of South Harting, all lay claim to being definately of the latter type, the villa, with varying degrees of probability.

Way back in the 19th century, the then Rector, Rev. Gordon, recorded that he had spotted a tessellated floor and substantial wall within the grounds of what was then the Rectory on North Lane, leading him to assert that this was the site of Harting’s Roman villa. But his claim has never been proven, and the site remains doubtful. Some time later, during grave-digging and again later during excavations for an extension, Roman pottery and tiles were found in the churchyard, suggesting that it was here that Harting’s villa may have once stood, but a small collection of finds a villa doth not make, therefore this too is to be treated with caution.

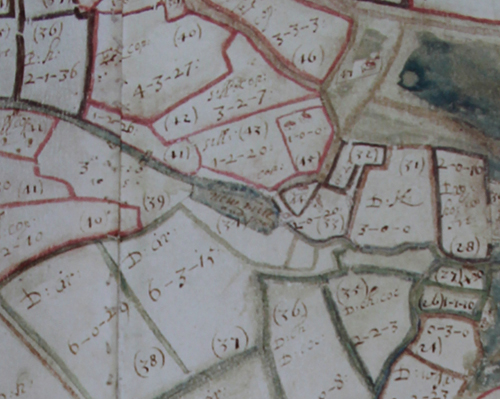

The third central site, however, relies on much firmer evidence. The land either side of New lane has long been known to contain Roman artefacts, ever since Brightwell, whose house “Bead Cottage” lay on the lane, dug rather surreptitiously in the field behind and found pottery, tile and iron objects, before being ordered to stop. But then, in the early 21st century, an aerial photograph taken for reasons that had nothing to do with archaeology, revealed the clear outline of the foundations of what is called a “winged corridor villa”, thereby establishing Harting’s first, and so far only, confirmed Roman villa. To date it has not been further investigated.

With the close of the Roman period, Harting enters its own archaeological “Dark Age”, with no known Saxon site lying within the parish. Light only begins to shine once more once we enter the medieval world of the Hussey family, centred on the village of South Harting.